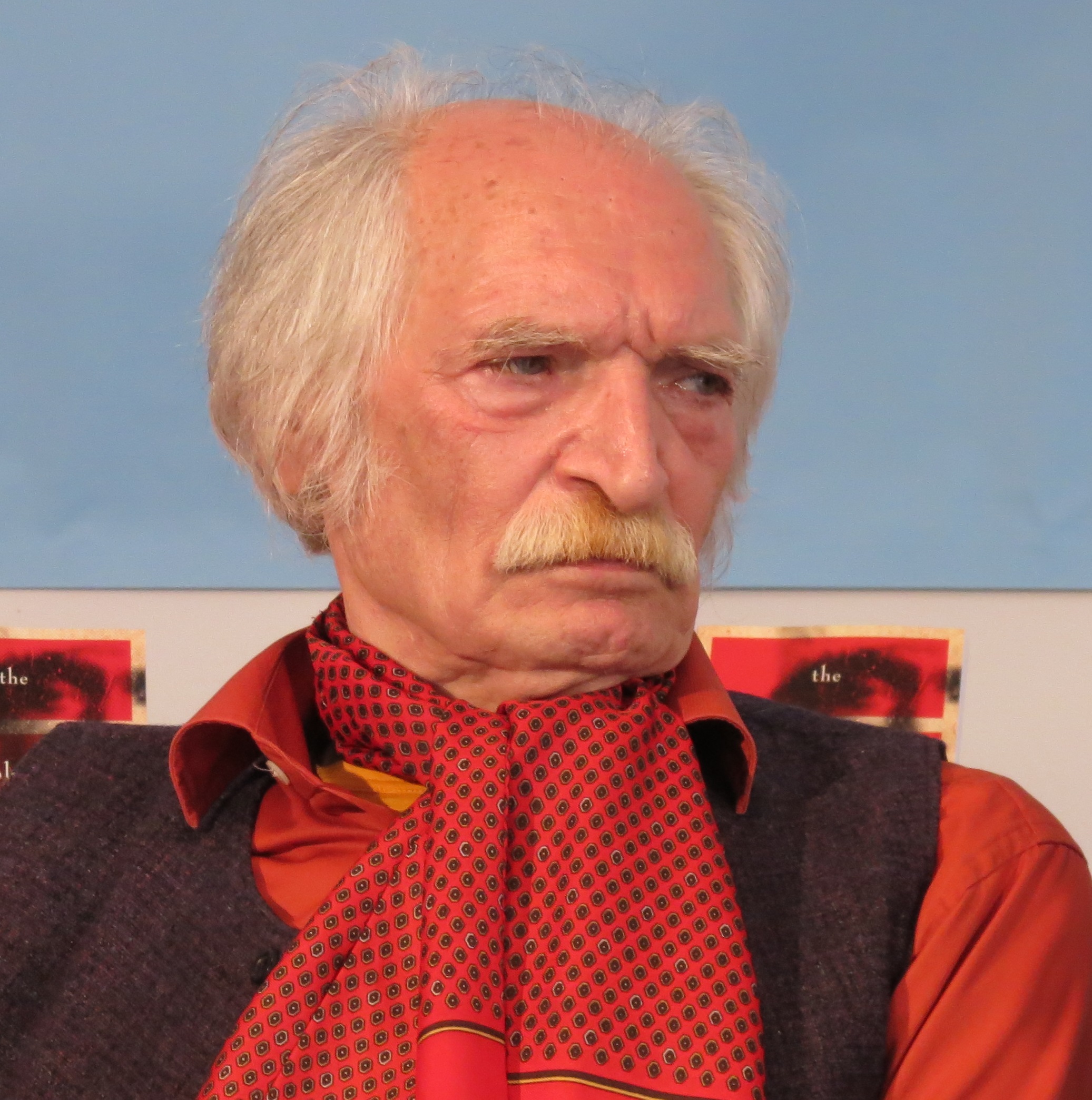

Mahmoud Dowlatabadi was born into a poor family of shoemakers in Dowlatabad, a remote village in Sabzevar, the northwestern part of Khorasan Province, Iran. He worked as a farmhand and attended Mas’ud Salman Elementary School. Books were a revelation to the young boy. He “read all the romances [available]… around the village”. He “read on the roof of the house with a lamp…read War and Peace that way” while living in Tehran. Though his father had little formal education, he introduced Dowlatabadi to the Persian classical poets, Saadi Shirazi, Hafez, and Ferdowsi. His father generally spoke in the language of the great poets.

Nahid Mozaffari, who edited a PEN anthology of Iranian literature, said that Dowlatabadi “has an incredible memory of folklore, which probably came from his days as an actor or from his origins, as somebody who didn’t have a formal education, who learned things by memorizing the local poetry and hearing the local stories.

As a teenager, Dowlatabadi took up a trade like his father and opened a barbershop. One afternoon, he found himself hopelessly bored. He closed the shop, gave the keys to a boy, and told him to tell his father, “Mahmoud’s left.” He caught a ride to Mashhad, where he worked for a year before leaving for Tehran to pursue theatre. Dowlatabadi worked there for a year before he could attend theatre classes. When he did, he rose to the top of his class, still doing numerous other jobs. He was an actor—and a shoemaker, barber, bicycle repairman, street barker, worker in cotton factory, and cinema ticket taker. Around this time he also ventured into journalism, fiction writing, and screenplays. He said in an interview “whenever I was done with work and wasn’t preoccupied with finding food and so on, I would sit down and just write”.

He performed Brecht (e.g. The Visions of Simone Machard), Arthur Miller (e.g. A View from the Bridge) and Bahram Beyzai (e.g. The Marionettes). He was arrested by the Savak, the Shah’s secret police force in 1974. Dowlatabad’s novels also attracted the attention of local police. When he asked what was his crime, they told him, “Nothing, but everyone we arrest seems to have copies of your novels so that makes you provocative to revolutionaries. He was in prison for two years.

Towards the end of his incarceration, Dowlatabadi said “The story of Missing Soluch came to me all at once, and I wrote the entire work in my head.” Dowlatabadi couldn’t write anything down while in prison. He “become restless”. One of the prisoners…said to him, ‘You used to be so good at putting up with prison, now why’re you so impatient?’ He replied that “my anxiety isn’t related to prison and all that came with it, but about something else entirely. I had to write this book.” When he was finally released, he wrote Missing Soluch in 70 nights. It later became his first novel published in English, preceding The Colonel.